While Governments are focusing on parameter R in their fight against COVID-19, recent studies about the virus’s nature show there is perhaps a better measure – parameter K, which can allow decision makers to manage the crisis more efficiently.

The spread characteristics of COVID-19 are different from the patterns we are familiar with from other viruses. Studies within the science literature point towards the need to realign our methods of tackling COVID-19’s unique spreading patterns.

The recent findings have major implications on the type of tests to be taken, the methods of epidemiological investigations, etc. Furthermore, the experience in the city of Bnei Brak, Israel during the months of March and April 2020 – when the “first wave” of COVID-19 struck – demonstrates how to apply efficient and precise measures, in line with the epidemiological picture now being revealed in scientific research.

This helps elucidate a matter currently at the center of debate: The now famed R parameter is an important epidemiological factor, but are we overlooking an even more crucial parameter which is a real operative measure for the virus’ level of contagiousness?

Shifting our Perspective from R to K

Over the past few months, various assumptions were made in an attempt to understand why parameter R – which has been widely touted as a key factor in understanding how the virus operates – has not provided the necessary information about the virus’ spreading nature and scale. It’s important to understand that R is an average measure of a pathogen’s contagiousness, or the mere number of susceptible people expected to become infected after being exposed to a person with the disease. The problem is this data is not as relevant as we hoped it would be due to the abnormal spreading nature of the novel virus.

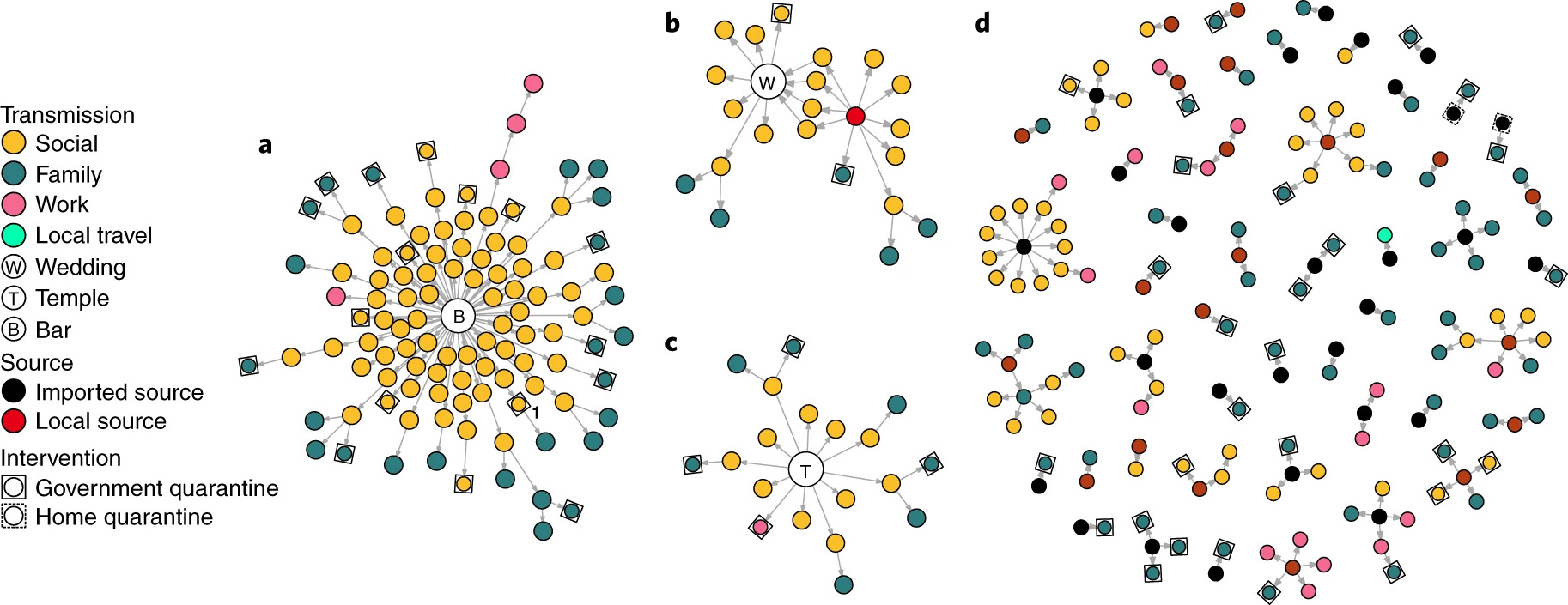

After months of intensive research and multiple epidemiological studies, it is now clear that COVID-19 is an over-dispersed pathogen with a tendency to spread in clusters. Hence, there are studies introducing parameter K, which in contrast to R measures the virus dispersion – whether the virus spreads in a steady manner, or in big bursts where one person can transmit the virus to many others at the same time and place. However, this is not being taken into account by Governments and the prevention measures taking place against the virus. That is a result of over-focusing on the R parameter, and turning it into an operative measure even though it didn’t help in predicting or preventing infections.

Due to COVID-19’s over-dispersed nature, measuring averages by parameter R is not sufficient in order to understand the dispersion of a phenomena. There are COVID-19 incidents in which a single person likely infected over 50 people in the room in just a few hours. But, at other times, COVID-19 can be surprisingly much less contagious. In addition, studies have shown that most people who are positive for COVID 19 are unlikely to transmit the virus to additional people. This imbalanced nature of the virus explains that just a bit of bad luck combined with a few super spreading events can produce dramatically different outcomes even between countries/cities with similar characteristics and circumstances. As such, parameter K will include critical data which will be missed focusing solely on R.

Adapting operative measure based on K

Is it possible to think of virus dispersion in two ways: Deterministic and stochastic. In a deterministic scenario, the spread of the virus is more linear and predictable. What happened yesterday could be a basis for what will happen tomorrow. In a stochastic one, randomness plays a key role and thus almost impossible to predict. Research has shown that super-dispersion events usually occur in closed surroundings that are not properly ventilated, and where people are gathering for a long time – this could be weddings, synagogues, gyms, and funerals.

According to The K method, which relies on the spread characteristics of the virus, there is both a need and a way to reverse the method of epidemiological investigations. If the emphasis is currently on the contacts whom a verified patient has produced and the insertion of those contacts for isolation, the goal should instead be to locate the person who infected the verified patient. Another aspect that should be emphasized is the importance of fast and affordable tests as opposed to slow PCR tests. Rapid testing may be less accurate but much more effective in measuring virus spread and infection events than they are at measuring individual infection.

During the peak of the “first wave” in Bnei Brak, the epidemiological investigations focused on identification of the COVID-19 exposure. Using the K method, we asked “Who transmitted the disease?” rather than automatically conducting a detailed investigation focused on the people who may have potentially been exposed to the COVID-19 carrier. This was done through creating trails of contact to identify the initial source of transmission. It appears to be the most efficient investigation approach in accordance with the way the COVID-19 spreads, that being in major events by clusters. Tracking down all contacts who were exposed to a COVID-19 positive patient since the day of infection could have been sufficient if the chances of transmission would have been more stable, like in the case of a regular flu – The fact is we are not dealing with anything close to regular.